Of late I have had little of anything much to do, but tie flies and perhaps think more than I should. Time does that for you, it leaves space to think and one can do too much of it.

But I have recently been working on filling a fly box with patterns in preparation of a new season, one where I hope I will find fishing near my doorstep and greater opportunity to enjoy it than I have managed previously.

There is something a little bit odd about this particular box though, because despite that it is entirely filled with dry flies, there isn’t a single hackle or hackle fibre in the box. My precious and limited supply of genetic capes and crisp saddles has remained untouched. To a point it is an experiment, although to be fair I know the patterns are effective; they are variations of trusted flies from the past. The tails of most of them are microfibbets taken from a much-abused paint brush, the remaining components of almost all the patterns are synthetic fibre and CDC.

And yet, even now, after close to five decades of tying flies and catching fish with them, I occasionally find myself consumed by doubt. They are not the flies of my youth; they don’t follow the formulae and specifications of fly tying with which I grew up. In short there is still a piece of my mind which questions the validity of what I am doing, the rules of the past still influencing my thoughts.

Rules are like that; they can promote consistency and order, but they can equally stifle experimentation, thought, design and improvement.

What if in the past everyone just sat back and decided that sails were the only way to power ships, or that thatch was the only way to roof a house?

What if Thomas Edison had thought the candle the apex of lighting development, or if Henry Ford imagined four horse power meant four horses?

Rules help us and stifle us in equal measure, often the more vociferous the voice commanding the rules the greater the impediment to progress. There can be few people in the history of fly fishing and fly tying more determined to regulate how things were done than Frederic Halford. Laying out all manner of regulations with little or no actual scientific purpose, probably not even any great measure of efficacy. Foolish affectations such as only fishing dry flies upstream, or only fishing to rising fish. Thankfully most of us have learned to ignore such foolish notions. And yet, even today, the standard, accepted means of tying a dry fly is unduly influenced by the opinions of a man who hasn’t walked the earth in over a hundred years.

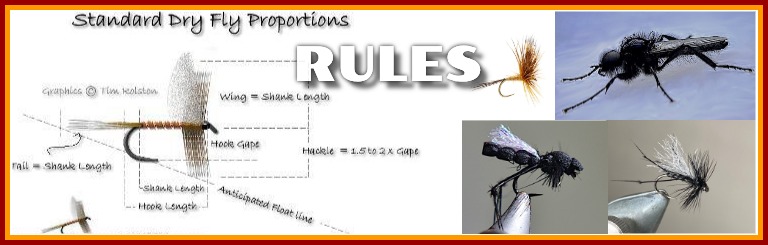

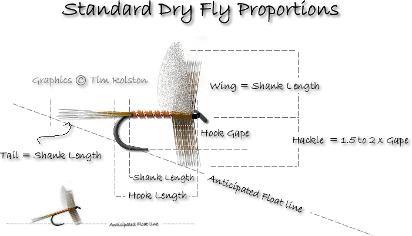

When most of us sit down at the vice those same “rules” still hold more sway than they should. The perpendicular wound cock hackle, the precise measurements of fibres, tails, wing height and all the rest of it. I have been just as guilty as the rest, I have published articles and books with diagrams describing “the correct way” to tie a dry fly. It is all, for the most part, a nonsense.

Yes, those oft stated proportions need to be followed to end up with a mechanically stable fly, but only because of the standard means of construction. Tie the hackles too long and the fly falls over, the tail too short and much the same will happen, have the wings oversized and the fly tips on its head, or spins the tippet into a rope. These are limitations of mechanical design and imitation and although we well understand that, we all too frequently find ourselves trapped by rules that we know we would be better to ignore.

Halford’s influence covered the globe, correspondence with Theordore Gordon in America meant that, what are known as “Catskill Dries”, really just follow much the same “rules” as laid down by Halford. Part of that is simply a result of the materials available at the time, but the influence lives on even now, and probably not for any good purpose.

Above, a diagram illustrating accepted proportions for a dry fly, taken from my book “Essential Fly Tying Techniques” (available on line from Smashwords just follow the link). . One hundred years on and I am still being influenced by Halford, yes the mechanics make some sense, but almost certainly don’t represent the best way to imitate a floating fly.

To be honest, the basic design is flawed, it doesn’t allow for imitation of larger wings in some patterns or shorter tails, and yet real mayflies (Ephemeroptera) show considerable variation in these dimensions. Not only that, but they don’t perform that well either.

The limitations of materials and design almost certainly mean that the “Father of Dry Fly Fishing”, was mostly, although apparently inadvertently, fishing “emergers” at best. This flaw is likely to have had as much to do with his success as anything else. It is nice to see images of this style of fly, balanced neatly on the hackle tips, poised on the surface, much like a miniature ballerina on point. The truth is that they simply don’t behave like that most, if any, of the time. It is a nice illusion, one that has persisted for years, but an illusion it most certainly is.

Moreover, the same basic layout then influenced imitations of totally unrelated insects, why would you tie a caddis pattern in the same basic format that you tied a mayfly? Why do the same for a stonefly, Hawthorne fly, or even a beetle? It doesn’t make sense and yet even now many of us are influenced by this nonsense. Make no mistake, frequently so am I and I feel foolish for it.

Surely there has to be a better way of imitating the stone fly in the top image, rather than use perpendicular hackle? It’s a nice pattern to be sure, it just doesn’t make sense to me that this is the best way to go. What about caddis flies? Does it make sense to tie patterns in the “Standard Mayfly Style” ?

As with the Henryville Special above, supposedly a caddis fly, nicely tied, but there can be little doubt that an Elk Hair or F fly would be a far better bet, if Trichoptera are on the water.

With reference to the top image of a real Hawthorne Fly, which of the patterns beneath it would you choose to fish? The influence of “standard fly tying” is still there, and in some small way, I still “like” the middle image better. I have been brainwashed into thinking that it looks prettier, because it follows those standard rules embedded in my head.

Of course, there have been plenty of innovators who have challenged the norm:

Caucci and Nastasi popularised the Comparadun, which looks absolutely nothing like a Catskill tie and doesn’t even use similar materials, but has proven super effective.

Someone, and it isn’t certain who, came up with the idea of the “parachute dry fly”, using the same basic materials but with the innovation of winding the hackle on a horizontal plane. The originator isn’t certain but the style was patented by an American William Brush in 1934. One assumes that has lapsed or a lot of us would be paying royalties.

The parachute style is infinitely more open to variation than the Catskill/Halford style, the wing can be near any length, the tails the same. It requires less hackle, likely provides a more realistic profile on the water, and is far less likely to twist up the tippet. For many, this style is still seen as rather outlandish and even now the proportions tend to follow Halford, for absolutely no good reason.

Hans Van Klinken’s original “Klinkhammer Special” had massive hackle dimensions compared to the standard model, and yet even now, many flies purportedly sold as “Klinkhammers” have reverted to standard proportions. So much so that I cannot find an image of a true original as described in Oliver Edward’s “Flytyers Masterclass”. It seems that instead of evolving, the proportions have devolved back to what is viewed as “standard”. It is as though the ghosts of Halford and Gordon still follow us and overly influence our thinking.

Certainly much innovation been facilitated by the arrival of “new” materials: foam, snowshoe hair, CDC, polyyarn and more, but still, those ingrained images of Catskill/Halford styles and proportions linger in our psyche as though cast in stone, as inflexible as they are illogical.

It is not so much that there has been no innovation, there have been plenty, with new concepts, designs and patterns, many of which are demonstrably better in some manner compared to the Catskill/Halford mantra, and yet they are still viewed by many as “outliers”, “not the real thing”, “oddities” if you will.

Even now those lingering doubts about proportions and materials still cloud our judgement. Go and search a popular website for dryfly patterns and just see how many still follow these antiquated rules.

This is the first image that comes up when searching “Dry Fly Selection”, there is a single parachute, no comparadun, snowshoe hair, CDC, or even an Elk Hair caddis in there. No Klinkhammer, no beetle, ant, F Fly, cricket, or hopper. There isn’t even a barbless pattern in that image. I think that we should have moved on a bit by now. I have to say that I don’t think that I have cast a Catskill style perpendicularly wound hackle fly in nearly twenty years, but the influence is still there, each time I sit at the vice, and I work hard to shake it off.

Part of the problem is that I like the “old school” flies, I still have, at some level, this foolish notion that they are “correctly tied”, that they are prettier than more modern designs, and they may well be, but how much of that is just that I have been brainwashed?

I like those flies, but I don’t fish them, at least very rarely, there are better, more imitative, less demanding, cheaper and easier to produce flies which will outfish them. And yet, even now, I fear that I am committing a mortal sin by talking about them.

If you found this piece, interesting, educational, amusing or simply entertaining you are encouraged to subscribe so as to be kept up to date with new posts and equally to take a look back at many articles posted on “The Fishing Gene” over the years.

You are of course most welcome to comment on this or any other posts on “The Fishing Gene Blog”.

Tim Rolston is the author of a number of books on fly fishing and flytying, available on line through Smashwords. If you wish to explore more just click on the image above to see what is available.

Tags: Comparadun, Dry Flies, F Fly, Fly Design, Frederic Halford, Guide Flies, Parachute Dry Fly, Tim Rolston

Leave a comment